THE FIRST SPACE TRAVELERS

Corinne Moore, Tech BD Lead

5 minute read

From microscopic water bears to mice and other mammals, quite a few species have experienced life in orbit. In today’s KMI Column, we’ll be answering the “when & why” of sending animals to space throughout humanity’s short spaceflight history, along with the benefits of current studies aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

Flight Setup

Before we dive into the specifics of each animal, let’s talk logistics. Depending on the type of animal, the seating requirements on the rocket would differ. Insects don’t take up much space and can typically be flown in vented vials like the Vented Fly Box (VFB). For larger bipedal mammals, the go-to was a seat with built-in harnesses and restraints. A similar method was used for canines, who were equipped with a harness and fasteners to secure them and prevent injury.

Fruit Fly

On February 20, 1947, the United States launched fruit flies aboard a V-2 ballistic missile, making the fruit fly the first animal in space and achieving an altitude of 109 kilometers in 190 seconds. The purpose of this experiment was to see how the fruit flies were impacted by radiation at high altitudes. Post-retrieval of the flies indicated no detectable changes or radiation damage. Studies continued with fruit flies well into the 2010s, with longer exposure showing the harmful effects of radiation being shorter lifespans, genetic mutations, impaired reproductive ability, and immune deficiencies as compared to flies that remained on Earth.

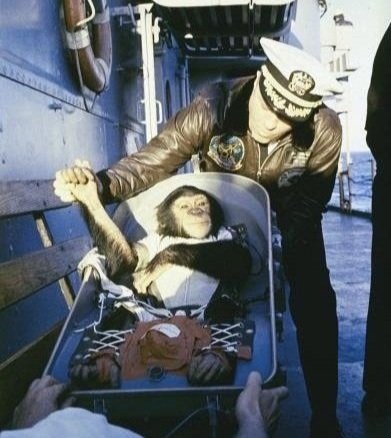

Rhesus Monkey

The United States was also the first to send a monkey into space, with the launch of Albert I in June of 1948. As monkeys are mammals with very similar systems to humans, sending them to space as a trial run for survivability made the most sense to scientists of the day. It wouldn’t be until after six Alberts in May of 1959 that the United States would welcome the return of a live subject from launch, with the return of Able (a rhesus monkey) and Baker (a squirrel monkey).

Dog

Russia was the first country to launch dogs into space. While Laika is remembered as the first dog to orbit the Earth, there were two that came before her: Dezik and Tsygan. On July 22, 1951, both of them rode an R-1V rocket and reached an altitude of approximately 110 km. Both of them survived their first flight, but Dezik perished in her second flight when the capsule’s parachute failed to deploy. Tsygan would go on to live a life as a comfortable house pet and mother of two litters.

Laika, as we’ve mentioned before, is the famous stray pup from Moscow who was the first to orbit the Earth. Her story is a sad one, however. Launched into orbit aboard the Sputnik 2, they knew she would not return. The craft wasn’t designed to survive reentry and in order to meet weight limits the scientists only planned for one meal to be included, despite the fact that Laika would run out of breathable air in seven days. Thankfully, her fate was somewhat kinder, and due to heat shield failures, she likely passed shortly after launch on her fourth or sixth orbit. Her story spurred on many discussions of animal rights and whether or not the testing of animals in space is a humane endeavor.

Laika’s fateful journey preceded the first successful orbit and living return of Belka and Strelka in August 1960. These two pups, along with two rats, a rabbit, and fruit flies flew aboard the Sputnik 5 and orbited the Earth 17 times, landing safely. In fact, when Strelka had puppies, one named Pushinka was sent to the Kennedy family at the White House, with a small Russian passport included. Belka and Strelka both lived to old age and passed peacefully.

Dog’s Best Friend

After these historic launches of Canis Lupus Familiaris (domestic dog), the Soviets sent Homo Sapien (semi-domestic man) Yuri Gagarin across the Karman line to orbit the Earth on April 12, 1961.

Cat

In 1963, France decided to throw their hat into the space race with suborbital flight testing featuring Félicette the cat. Over the course of two years, fourteen cats were given “astronaut training” for this flight, including centrifuge and confinement testing. Félicette reached an altitude no cat had ever dreamed of before (157 km) and was in space for about five minutes. The capsule landing via parachute was a success and she survived the test unharmed. Two months later, scientists decided to euthanize her and perform an autopsy to see if they could learn anything further. They did not learn anything new, and admitted so. Gone, but not forgotten, Félicette is memorialized by a statue crowdfunded by fellow cat lover Matthew Serge Guy at the International Space University Campus in Strasbourg, France.

Honorable Mentions

We can’t forget the lesser-known critters of space history who made their contributions to science! These include bullfrogs, nematodes, fish, spiders, newts, tortoises, stick insects, brine shrimp, sand desert beetles, guinea pigs, crickets, snails, jellyfish, and chicken embryos. As much of an animal lover as I am, I was really hoping “bugs in space” wouldn’t be a thing.

Animal Studies Today and Policies

As one of the first creatures to be sent to space in the 1950s, today mice are the highest-order animals sent to the ISS for study. Among the many benefits of utilizing mice in space is their ability to adapt quickly to the microgravity environment. Like many other small rodents, such as hamsters and guinea pigs, in captivity mice enjoy getting their exercise. Microgravity makes the standard method of a cage wheel a bit impractical, but that didn’t stop this group of mice from getting their steps in. After only 7-10 days, they adjusted to their new way of life and used their environment to run a “zero-G racetrack” around their cage.

One particular study on the ISS dubbed their group “Mighty Mice,” with these brave rodents sent to the ISS to study the impact of extended microgravity exposure on muscle mass in a living organism with genetic modifications to inhibit certain proteins. What we’ve learned so far is already contributing to knowledge on how we can best treat conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta, as well as the deterioration of muscle and bone strength that occurs in those with limited mobility. Many other conditions, including muscular dystrophy, osteoporosis, cancer, heart disease, sepsis, and AIDS, can cause muscle wasting and those with them would greatly benefit from more targeted therapies.

The standards for the care of animals during space testing have changed dramatically since the early days of spaceflight. At NASA, the Flight Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (FIACUC) oversees animal research and humane treatment of the animals in their care. There are three basic principles listed: respect for life, societal benefit, and nonmaleficence. All together these mean that living, sentient creatures must be treated with respect and all efforts must be made to “minimize distress, pain, and suffering.” Even in cases where those two conditions are met, tests should only continue if they are justified by what can be gained from them, measured against any distress to the creature.

The debate for and against animal testing has been, and will likely continue to be, a hot topic amongst both researchers and the general public. The bottom line, for this author anyway, is that now that we know better, we can and must do better for our animal friends.

Recommended column to read next: Biomimetics and Living Machines: How Lessons from Nature can Transform Technology