Is Anybody Out There? Fermi’s Paradox and Alien Existence

MARIA BERISHAJ, PROJECT MANAGING ASSOCIATE

5 minute read

Long before humans realized the potential of space travel, before telescopes had even been built, the notion of life amidst the sea of stars was a thought of many. Up there with, “what is the meaning of life?”, the question of, “do aliens exist?”, must be one of the most asked questions in history. It’s been approached by leading scientists and by children's educational programs. As humans advance in our understanding of mathematics, physics, and the world, coupled with our technological exploration, we have discovered that the Earth may not be so unique. There are billions of Earth-sized planets in zones conducive to life. So if there’s a high chance aliens are out there, where are they?

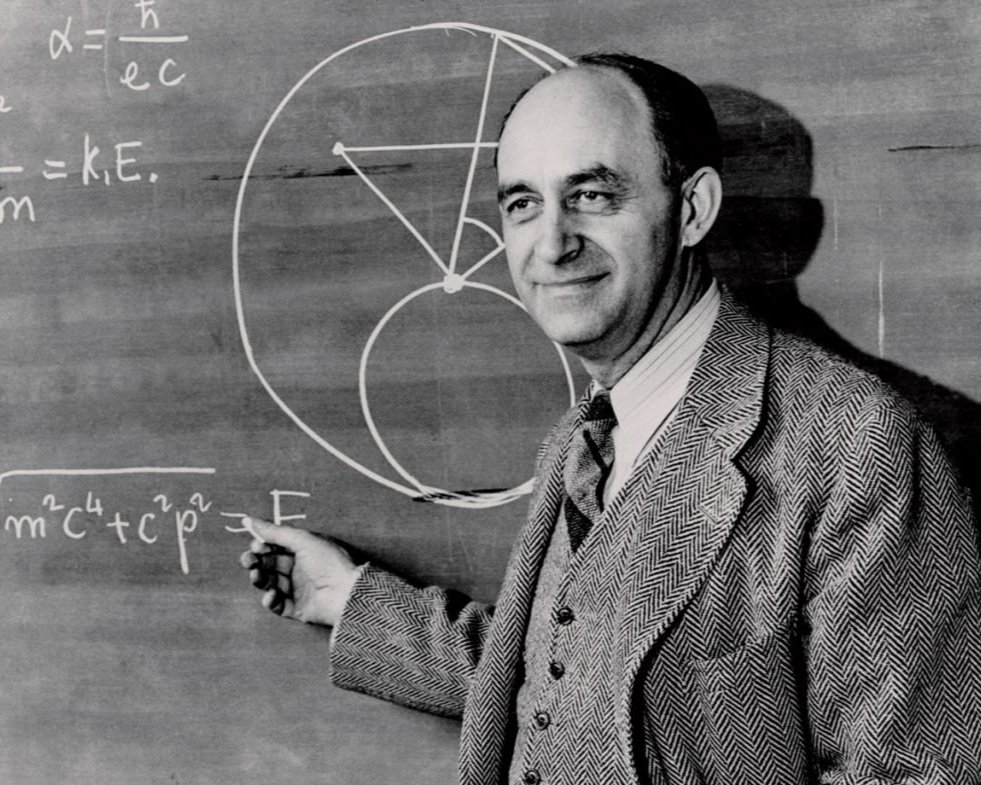

The paradox that arises from the statistical likelihood of aliens coupled with the apparent lack of their existence is known as Fermi’s Paradox. The idea was established in the summer of 1950 when physicist Enrico Fermi was conversing with fellow physicists on the topic of aliens and blurted out, “But where is everybody?” To get to the root of this paradox, let's first understand the statistical likelihood of the existence of aliens. Focusing on just the Milky Way, there are about 200-400 billion stars. Of these, there are approximately 20 billion sun-like stars with research suggesting that about 20% of these stars have an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone. The habitable zone is a range of distance from a star that is conducive for life, specifically that which allows for the existence of liquid water. The Earth is an example of a planetary body in a habitable zone. Along with other complicated processes (keep reading if you want to find out), our distance from the sun was essential in the formation of any life, followed by the seemingly rare intelligent life of humanity. Thus there could be around 4 billion planets in the Milky Way alone that are about the size of Earth and located in the prime location for life to form.

In fact, astrophysicist Frank Drake formulated a probabilistic equation, called the Drake equation, that estimates the number of active and communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way. In the figure below, Drake’s equation incorporates many parameters that are still unknown to us. Current estimates, while varying greatly due to estimations of these unknown parameters, have yielded numbers as great as 15,600,000 extraterrestrial civilizations.

Drake’s Equation via Scientific American

If this number isn’t convincing enough, there is also the aspect that Earth is estimated to be 4.5 billion years old, which is quite young in comparison to the estimated age of the universe: 13.8 billion years. Human civilizations have been around for about 12,000 years, a very small blip in the Universe’s timeline. Intelligent life not only has the opportunity to exist elsewhere amongst many ideal locations in space, but has also had plenty of time to develop to either the level of modern humans or far beyond. Based on the size of the Milky Way, if an intelligent species were to send out a few spaceships to other habitable planets and colonize those while repeating this process for each planet that gets colonized, it could theoretically be colonized in just a couple of million years. Yet 13.8 billion have passed, with not a single piece of evidence that anyone else is out there. This uncomfortable observation gives us a paradox. How is it that statistically speaking the likelihood of intelligent life existing seems great, yet we have been unable to observe any actual evidence?

With such a grand question, potential solutions must be, and have been, thought of. One potential resolution has been coined as the Great Filter. Earth went through quite a complex process to get to the point where it is now: a carrier of intelligent life. From a star system starting with the right building blocks, to forming complex single-cell life, to multi-cell life, to tool-using animals with intelligence, each of these stages can be thought of as a “filter” necessary to pass through for a planet to be able to sustain intelligent life. The Great Filter is the notion that for many potential life-carrying planets, there is some “filter” (i.e. some process) that is never achieved, resulting in a much smaller likelihood that aliens exist. Maybe this filtering is so strong that humans are the only intelligent life in this Universe. Additionally, a filter doesn’t need to make life rare, but could be a filter inevitable for the destruction of all intelligent life prior to the phase of space colonization. Whether it is mutual destruction (such as a nuclear war), environmental problems like climate change, or an undiscovered technological advancement that destroys humans, there could be a barrier preventing all intelligent life, including us here on Earth, from colonizing space.

Resolutions such as the Great Filter would mean space colonization is very rare, or even impossible. This is not the only way to look at the lack of evidence. Another resolution promotes the idea that alien civilizations, while having the ability to communicate with Earthlings or colonize the Milky Way, have simply chosen not to. If this were the case the possible reasons are plenty, such as the possibility that alien civilizations remain quiet for their own safety (maybe there’s a big bad out there annihilating any alien species making itself known) or that humans just simply aren't interesting enough. Some theorists even go as far as to say aliens have visited Earth and communicated with us, we just haven't properly looked at the evidence, if any was left behind.

The complexity of this paradox and the potential resolutions are burdened by too many unknowns. Due to human limitations with current space travel and technology, we ultimately don’t know what’s truly possible. Maybe we are alone, or maybe there is a component in the ways of the universe yet to be understood, but one can’t help but ponder the implications of Fermi’s Paradox.

Recommended column to read next: What Makes a Good Chart